This is probably the cringe-most article I might have written because it is about a daily soap — that too, a Marathi daily soap.

Before you accuse me of anything, here is my anticipatory defense. Firstly, the series is the easiest to watch. By easy, I mean it is easy on my time. At the end of every episode, we are given a glimpse of the next day’s episode. The thirty-second preview is literally the entire episode. Believe me, when I say literally, I mean literal literally! Besides the events in the preview, the rest of the episode is riff-raff, people walking from point A to point B, and mindless chatter. Twenty-three minutes of your life are saved by watching a thirty-second clip — enough to keep track of the story.

Secondly, if you watch it online, it is free to view (maybe, this should have been the first reason), and each episode comes with a one-line description of the episode. Now it is your choice whether to see the thirty-second clip or read a line.

With that, let’s examine the artifact itself. It is basically the story of a housewife, mother of three, simpleton — Arundhati. For twenty-five years, she is feeding her children, tending to her in-laws, ensuring a smooth domestic life for her husband. Since she is a ‘mere’ housewife, nobody appreciates her. The work she does, cooking, cleaning, parenting, is considered menial. Her talents, like singing, are considered ordinary. Her knowledge is deemed to be useless in the real world because she earns no money from it. Hence, the title, आई कुठे काय करते; implies Mom doesn’t do anything.

With that, let’s examine the artifact itself. It is basically the story of a housewife, mother of three, simpleton — Arundhati. For twenty-five years, she is feeding her children, tending to her in-laws, ensuring a smooth domestic life for her husband. Since she is a ‘mere’ housewife, nobody appreciates her. The work she does, cooking, cleaning, parenting, is considered menial. Her talents, like singing, are considered ordinary. Her knowledge is deemed to be useless in the real world because she earns no money from it. Hence, the title, आई कुठे काय करते; implies Mom doesn’t do anything.

This idyllic existence of Arundhati is jolted when she comes to know (After 180 episodes) that her husband of twenty-five years is having an affair with an office colleague. Like a house of cards, the basis for her life collapses in a heap.

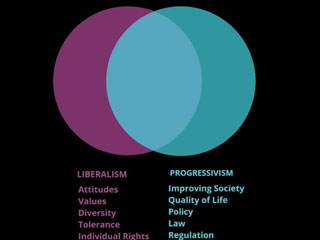

A solid premise with progressive undertones. Divorce in young couples is considered somewhat simple. In comparison, separation while having children in their twenties is challenging. Instead of reconciling and waiting for her husband to realise his folly, Arundhati decides to take the matter into her own hands. She moves for divorce. Not out of anger but out of a desire to search for a new identity. Her mother-in-law and elder son are traditionalists; they want the affair to be swept under the carpet. They feel Arundhati should forgive her husband and accept him back. At its core, it is a clash of values and attitudes.

The serial is a dose in feminism, progressivism, and liberal values. How often we have heard wives wronged by her husband’s affairs are advised to forgive and forget for ‘the sake of her children.’ Arundhati challenges this notion about the ‘welfare of children.’ She says if she stays quiet now, what example is she creating for her daughter — to accept abuse of trust in a relationship!

The serial is a dose in feminism, progressivism, and liberal values. How often we have heard wives wronged by her husband’s affairs are advised to forgive and forget for ‘the sake of her children.’ Arundhati challenges this notion about the ‘welfare of children.’ She says if she stays quiet now, what example is she creating for her daughter — to accept abuse of trust in a relationship!

So far, so good. Interesting premise, at least something novel for the Marathi audience. But then, the show is also a case study in how the daily soap format can derail the best of intentions. The journey of Arundhati becomes the journey of all characters in the serial. Like picking a lottery sequence, trouble hits each character, the elder son, the daughter, the younger son, the grandfather, the grandmother, the mistress, the mistress’s husband… You get the gist. Instead of focusing on rebuilding her identity, Arundhati becomes solver-in-chief for the problems of others. Currently, the serial is inching towards the four hundred mark, and the divorce is yet to be finalized!

Now drifting around your story is one thing, but drifting away from your values is beyond puzzling. How can a progressive, liberal, modern story allow for superstition?

The lamp goes off, an accident happens. Oil from the lamp spills, another accident occurs, the number of lamps are not of the required quantity — you guessed it right; accident happens. So somebody get them a LED lamp.

And don’t tell me this does not have an effect on the masses. During my school days, a popular Hindi ‘Saas-Bahu’ serial had an obsession with prayer beads. Every time the Jaap-mala broke into multiple slow-motion replays of the beads scattering, it resulted in the passing away of some character. The association was so profound that my friend tried to buy immortality during the following Ramadan by getting a Misbaha woven with a steel wire instead of threads.

We can have progressivism but only this much progressivism, with allowances for irrationality.

On an interesting note, the serial contributes to creating a Geographical Information System (GIS) map of Indian progressivism. Arundhati’s story is not original. Yes, it is a story of millions of wives across India; however, more importantly, it is a story adapted from a Bengali soap (Sreemoyee.) From Marathi, the serial has moved to the national shores of Hindi (apologies to my south Indian friends) in the form of Anupamaa (do emphasize on the ‘maa.’)

By being the market leader, Bengali Arundhati is already divorced career-woman and also has a possible love interest in her life. Marathi Arundhati is probably still pondering whether her culture can allow for the introduction of a love interest. In general, she is a pondering ‘being,’ She is nearing the four hundred episode mark, but she is yet to get a divorce. Mallu Arundhati is not a slow person; before hitting the triple century mark, she is already divorced, has a new career and is exploring a love interest. In the Venn Diagram of things, Telugu Arundhati has crossed the three hundred mark, is yet to finalise the divorce, and has a love interest from her past in the mix of things. Tamil Arundhati was last to the party; others have a six-month head-start over her. So she is still embattling the nitty-gritty of divorce. Despite being equally late, Hindi Arundhati is done with the divorce and introduced a love interest. However, it has turned out that the love interest was a trope to evoke jealousy in Arundhati’s husband and create FOMO (a Fear Of Missing Out.) Devanagri versions are evaluating the possibility of re-patching Arundhati’s marriage. Whereas the Dravidian versions are more eager for Arundhati to have a fledging career. Whereas the Kannada Arundhati is in a different zone altogether. There Goddess Durga has given darshan in her flesh to guide Arundhati through her troubles.

By being the market leader, Bengali Arundhati is already divorced career-woman and also has a possible love interest in her life. Marathi Arundhati is probably still pondering whether her culture can allow for the introduction of a love interest. In general, she is a pondering ‘being,’ She is nearing the four hundred episode mark, but she is yet to get a divorce. Mallu Arundhati is not a slow person; before hitting the triple century mark, she is already divorced, has a new career and is exploring a love interest. In the Venn Diagram of things, Telugu Arundhati has crossed the three hundred mark, is yet to finalise the divorce, and has a love interest from her past in the mix of things. Tamil Arundhati was last to the party; others have a six-month head-start over her. So she is still embattling the nitty-gritty of divorce. Despite being equally late, Hindi Arundhati is done with the divorce and introduced a love interest. However, it has turned out that the love interest was a trope to evoke jealousy in Arundhati’s husband and create FOMO (a Fear Of Missing Out.) Devanagri versions are evaluating the possibility of re-patching Arundhati’s marriage. Whereas the Dravidian versions are more eager for Arundhati to have a fledging career. Whereas the Kannada Arundhati is in a different zone altogether. There Goddess Durga has given darshan in her flesh to guide Arundhati through her troubles.

Issues across India are similar and yet different. However, one aspect unifies the diversity of Indian television — A dearth of original material. Just add one step of ‘translate’ between copy and paste. Would I recommend you to watch this series? Here is the thing, I began watching this serial around the one-eighty mark. Currently, it is hovering around three eighty. Going by my thirty-second routine, I have given it a good hundred minutes of my life for those two hundred odd episodes. It is ninety-nine minutes thirty seconds more than what the serial deserves. Plus, unlike me, you have the benefit of this article. I hope you have your answer.

Since the series is made-remade with different POVs, with all possible local flavours, do you think will Indian storytelling be influenced by the influx of Netflix? Ekta Kapoor released the Sas-Bahu Genie, will Netflix (and likes) undo it? or may be replace it?