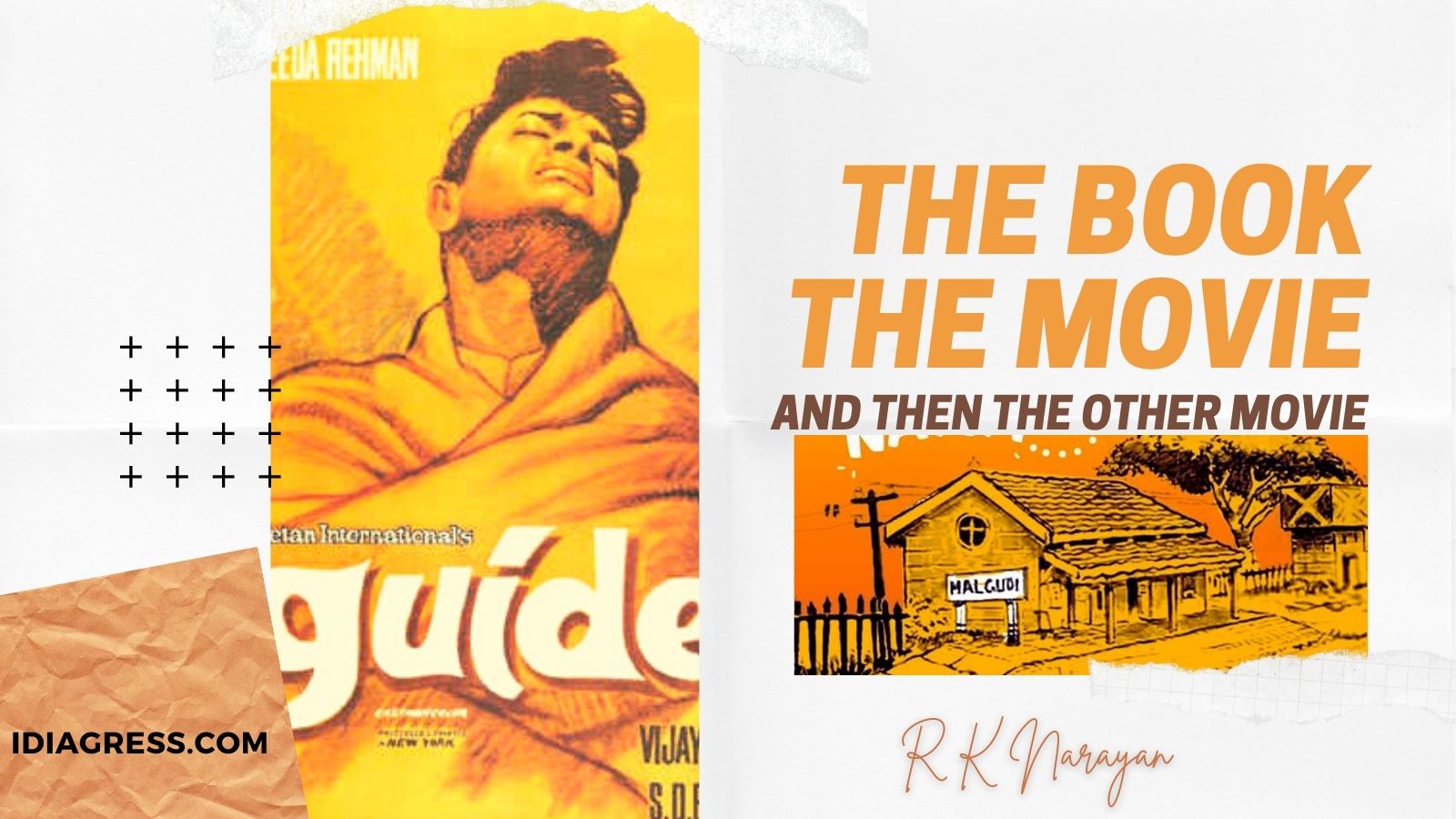

When I first saw the movie ‘Guide,’ I was enthralled by the arc of Raju, his catharsis, and almost a Valmiki’an transformation. It made me wonder – Why isn’t this adapted into an Oscar-winning Hollywood movie!

Well, some people did try, and let’s just say that some layouts look good on architectural paper, but, in a brick and stone avatar, leave a lot to be desired.

The original seed for the movies came from the Malgudi connection of R K Narayan, penned as ‘The Guide.’ Malgudi, for any kid of the nineties, is the home of ‘Swami’ and his friends. A childish abode with some ‘marma‘ laden stories delivered in a very soft punch manner. Sweet stories are set in the town of Malgudi, a town best described as ‘innocent.’

The original seed for the movies came from the Malgudi connection of R K Narayan, penned as ‘The Guide.’ Malgudi, for any kid of the nineties, is the home of ‘Swami’ and his friends. A childish abode with some ‘marma‘ laden stories delivered in a very soft punch manner. Sweet stories are set in the town of Malgudi, a town best described as ‘innocent.’

Hence, it was a big surprise to find that the story of the local guide of this town is laden with mature themes of infidelity, moral corruption, and borderline religious fraud.

The book is a linear arc of ‘Raju,’ a guide cum shopkeeper at Malgudi station. Just to clarify, the narration is non-linear, encompassing a series of flashbacks and flash-forwards. However, the underlying story is linear, almost a birth to death biography of ‘Raju.’

Since I was reading the book after watching the movie, I read Raju’s every spoken word in the characteristically wavy, boisterous tone of the great Dev Sahaab. In my mind, Raju is Dev and Dev is Raju, much in the fashion that Amar is Vinaay and Vinaay is Amar. We begin with Raju under the tutelage of his father as he graduates into a sweet-talking shop. Raju embodies the quintessential Indian, and dare I might say, a quintessential Punekar – throwing on the fly, made up fiction as deep, insightful facts. The ‘Indian’ guide is not satisfied by merely narrating the facts, like this old fort of a building is the former residence of the Peshwas of Pune. The ‘Indian’ guide has to accentuate and tell that every new moon night, at the third hour after midnight, we can still hear the cries of “Kaka, mala Vaachva” as a young Narayanrao Peshwa is re-assassinated, and how all of this ties up into a Marathi proverb, “Dha cha Ma Karu Naka.” Artistic license or misconstruction, the jury is out on this matter.

Raju, as the guide, is a sweet-talking mercenary targeting the pockets of clients, his motto -“Sabse Bada Rupaiya.” This free-spirited animal gets entangled with a married lady. Enchanted by Rosie’s beauty, Raju pursues her and becomes the reason for Rosie’s split from her husband, Marco. Raju then elopes with Rosie and begins living with her, which in today’s parlance can be referred to as a ‘Live-in relationship.’ A behavior that will be severely frowned upon in contemporary times. Imagine the kind of disapproval it must have received in 1958*.

Thus, it is understandable. When the Anand brothers decided to adapt the story into a Hindi movie, Raju had to be whitewashed to become suitable for its lead, Dev Anand. Raju of the film discards materialism and turns into a kind-hearted, mellow, and generous being. Dev Anand is the savior, and Rosie needs to be saved. She needs to be protected from her cold-hearted, ever suspicious, abusive, and treacherous husband. Marco of the book, in contrast, is a generous person, an academic, with liberal values for having dared to marry outside his circle. His only fault from the book is that he is too much interested in his work, the higher purpose of uncovering the region’s archaeological history. Family matters bore him, weigh him down, but he was not abusive. He often comes out as a considerate man. In other words, the Marco of the words in the story is more human than the Marco that lights up the silver screen.

The Guide is the story of the ‘Discovery of Raju.’ and you might think that by diluting the grey side of Raju, the movie does a disservice to the whole journey of Raju. However, the genius of the film is that it enhances the palette rather than diminishing it.

To cast Raju as the savior, Rosie needs a more extended character graph to justify her as the trodden. The Raju Rosie relationship in the book challenges both moral and societal norms. However, in the film, the orthodoxy of society is pitted against the moral generosity of Raju. Shouldn’t divorced or abandoned wives have another chance?

The Gaffoor of the book sure spews out some cautionary tales to warn off Raju but is happy to slide into the background once his commission is paid. However, the Gaffoor of the film is now a friend who misses and longs for his pal. In similar ways, the film becomes the journey of several characters, than just the lead.

Raju’s relationship with Nalini (transformed and successful dancer avatar of Rosie) never reconciles in the book. Built on lust, interlaced with opportunism, with constant swapping of master-slave roles, their relationship seems doomed. R K Narayan’s Raju is always adrift of the shore, and his every paddle takes him further away. It is his destiny to break away from all bonds and achieve a complete sense of directionlessness. What happens of the other characters —we don’t know; we are invested only in the journey of Raju.

In the film, Raju, Raju’s mother, Nalini, Raju’s friends all have to remain intertwined because Raju is not morally decadent. Raju’s fracturing with Nalini is based on misunderstandings and decades-old ideas of marital egos, AKA Abhimaan (Woman earning more than the Man.) Raju and Nalini’s love is not laced with dependencies. Hence, when the fracture happens, Nalini is equally distraught and reflective.

Post-breakup, the plot of the book and the film converge. Raju becomes a pseudo hermit in a stowaway village. He uses a mix of common sense, ideas of religion, and his sweet-talking methods to arbitrate issues around the village. It takes so little work from his side to elevate Raju as a Godman. Isn’t this so true? India is a land where people are searching for the next Godman. They want a savior, a sadhu, the next person, where they can transfer the burden of responsibility. Raju relishes the newfound role; it gives him both respect and means of sustenance.

Then, in a move of dark comedy, which can outshine any modern web series. Raju is forced into a twelve-day fast to appease the Rain-Gods and end the village’s drought.

Herein, the plots again diverge. Raju of the book is comically forced into the fast, and it is most likely the lack of nutrients that keeps him steadfast. However, Raju of the film embraces the fast and starts to face his inner demons. The news of the fast spreads, Raju becomes the Swami on a water mission. The book stays close to its dark comic undertones as it describes the idyllic setting of the fast in an almost Peepli Live manner. The film, however, takes a grimmer turn.

The inner soul of Raju projected on the screen, talking with itself, drawing upon the notions of ‘The Gita’ imparts deep philosophical meaning. Not just the dialog, the film uses visuals to indulge in ever deeper themes. One scene in this sequence is philosophical gold.

Nalini, alerted by several newspaper photographs of Swami Raju, embarks on a journey to meet him. Her car can take her only thus far in the barren landscape, and she has to afoot the remainder of the journey. The successful dancer arrives at the scene in full pomp and glamour, laden with shiny jewels. However, in the scorching sun, in the intolerable heat, the gems are a burden. In her desire to meet ‘her’ Raju, Nalini removes the jewels one by one, at times even carelessly, allowing the pieces to fall to the ground. In a drought wherein water is the real gold, no one cares for the metal. Gold and diamond are what they are, metal and stone, part of the earth.

Nalini, alerted by several newspaper photographs of Swami Raju, embarks on a journey to meet him. Her car can take her only thus far in the barren landscape, and she has to afoot the remainder of the journey. The successful dancer arrives at the scene in full pomp and glamour, laden with shiny jewels. However, in the scorching sun, in the intolerable heat, the gems are a burden. In her desire to meet ‘her’ Raju, Nalini removes the jewels one by one, at times even carelessly, allowing the pieces to fall to the ground. In a drought wherein water is the real gold, no one cares for the metal. Gold and diamond are what they are, metal and stone, part of the earth.

This scene is even more significant because the earlier rift between Nalini and Raju had occurred over some pieces of jewelry. The same pieces that everyone is allowing to fall to the ground without even a hint of concern. The filmmakers deliver a powerful message very subtlely using metaphors.

In more than one way, the movie’s last fifteen minutes add meaning and depth to the entire narration of over two hours. They contextualize everything and bring everything together. From a simple story, it transforms into profound metaphysical meditations. In a sense, the film weaves itself into a fable: like the Panchatantra — seemingly simple stories with profound conclusions.

And anything more, Oh Yes! The English version of the film. You need to understand that whatever we have discussed in the last minutes of the Hindi film is ‘absent’ in the English adaptation.

Nalini arrives at the final scene in a jeep, whose bumper almost touches Raju’s feet. In an interview, Waheeda Rehman (Nalini) remarked that she refused a request from the director of the Hollywood version. He wanted a shot of her kissing the top of the cobra in a dance sequence. It seems they were chasing an ‘exotic’ story, trying to adapt it to suit the audience’s tastes and pander to their notions. They lacked the courage to serve an authentic dish. Maybe a revived’ Guide’ might fare better in today’s time wherein local stories and narratives are appreciated worldwide. Then again, can we really top an already well-made classic!

One movie that i need to re-watch many more times just to understand the various layers.

another dev anand movie! you should start a dev anand fan club

thanks, interesting read