Vyasa’s epic tale becomes more menacing as it moves from Dvapur Yuga to Kali Yuga. Honor has left the stage; warriors don’t face each other by the rules of war; instead, they scheme via proxies and assassins. At one level, you might think that this is a simple re-telling of the tale in a modern context. However, the writer Girish Karnad is leading a two-pronged attack. He is critiquing the ancient myth by showcasing its absurdities using today’s situations. And, at the same time, he is hitting hard at today’s elites and the dryness of the industrial world, using the Mahabharata.

One caveat before we proceed to dive into Kalyug. The movie presumes your familiarity with the characters, themes, and critical events of the Mahabharata. It does not waste time in setting up the stage. A simple family tree shown at the start of the movie sets the ball rolling. The film is one event after another, like a spray from a machine gun. So, if you have no background on the epic, the movie will feel like a set of disjointed scenes without transition.

One caveat before we proceed to dive into Kalyug. The movie presumes your familiarity with the characters, themes, and critical events of the Mahabharata. It does not waste time in setting up the stage. A simple family tree shown at the start of the movie sets the ball rolling. The film is one event after another, like a spray from a machine gun. So, if you have no background on the epic, the movie will feel like a set of disjointed scenes without transition.

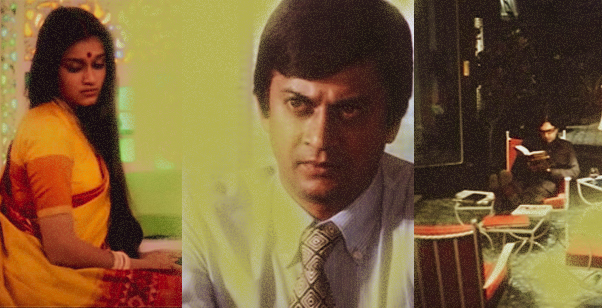

Once you accept the theme, the movie becomes an exercise in drawing parallels and deviations from the epic. The film does away with certain characters (Nakul, Sahdev, Drona, the ninety-eight Kauravas) and focuses on the conflict between families. Dharamraj, Balraj, Bharatraj (Arjuna) on one side, Dhanraj (Duryodhana), Sandeepraj with Karan Singh on the other side. The Pitamah of the two families, Bhisham Chand and Savitri (Kunti), hold on to family secrets and shames.

Tracking the deviations, we can’t help but notice the tectonic shift in Krishna. Kishan Chand of today is not eloquent on virtues and is not interested in delivering a treatise on Dharma. Instead, he is motivated by ‘self.’ He chooses the Pandavas because his sister Supriya (Draupadi) is married to Dharamraj. He cements this partnership further by marrying his Daughter (Subhadra) to Bharatraj. Yes, Kishan Chand matches his sister and his daughter to brothers of the same household. If we were to miss this absurdity, we are reminded about it in a terse tone by Draupadi.

Shyam Benegal and Girish Karnad use Draupadi to showcase the entitlement felt by today’s elites. Supriya nonchalantly mentions that Karan Singh wanted to marry her. She states this not because she has a soft corner for Karan. But to use it as an assertion of her superiority over the orphan. When income tax officers raid their homes and go through her personal belongings, she views this as an insult. She is not interested in the right or wrong of the raid. Her anger is fueled by the emotion of “How can they do this to us?”. How can a lowly tax officer even think of interfering in her life? After all, it is the privilege of those like her to control those below them. This is her Vastraharan.

Who is right or wrong in the tale? In the narration of the ancient legend, the Pandavas are on the side of Dharma. We take our presumptions into the movie, only to find them being dismantled piece by piece. The Pandavas are scheming. They use trickery to get hold of the industrial secrets of Kauravas. Their actions are clearly destroying the existence and legitimacy of the Kaurav enterprise. We see the Kauravas merely responding to the backstabbing by conjuring up a strike in the Pandava camp. The creators intentionally break the facade of Dharma on the side of Pandavas.

In the age of Kaliyuga, there is no Dharma; there are just winners and losers.

Soon enough, we realize that the writer is playing with our knowledge of the Mahabharata. As he deviates from the themes of the Mahabharata, he carefully maintains parallelism with the events of the Mahabharata. The wrongful death of Abhimanyu (Balraj’s son) remains a cowardly murder by Dhanraj. Karan’s murder occurs while he is fixing the punctured tire of his car. A lofty parallel is contrasting the depth of the movie. In general, the similarities stay at the surface, reminding us that this is the war of Kurushetra. At the same time, at the depths, we traverse the darkness of human relationships. The two families with knives at each other’s throats mingle effortlessly at weddings and social events—the absurdity of the Indian joint family culture.

Another human relationship: Marriage is dealt with a subtle underhand of all times. We see ‘noise’ in relationships. A calm, generally restrained Dharamraj is married to the volatile and ambitious Supriya. Supriya has a special connection with Bharatraj; both are ambitious, intelligent, and possess ruthless energy. Yet, Supriya has to watch Bharatraj getting married to her own niece, Subhadra. Subhadra is naive, enjoys the fine things of life; music is her comfort. In a similar vein, the orphan Karan is ironically the most cultured of the lost. He has a passion for sports, western classical music, enjoys his moments of comfort. Subhadra admires Karan but never thinks of him as a husband because she has been conditioned to be the cog that shall cement an alliance. In one scene, Subhadra, Bharatraj, and Karan meet in a hotel. Bharataj is raging with vile thoughts towards Karan. However, Karan approaches the couple, greets them, compliments the lady, and politely takes leave. Yet, everyone in the family treats Karan Singh as inferior to them. They disrespect him by refusing to shake hands and use the most grudging of tones while talking to him.

In one sense, Mahabharata is the tragedy of innocents like Karan, Subhadra, and Abhimanyu. Guided by social conditioning and a false sense of loyalty, they meet their doom. For Karan, the path is the most torturous. One of the best scenes in Indian cinema is when Kunti reveals the truth of his birth of Karan Singh. A scene where a superfluous writer like me would be tempted to spend lines and lines traversing the tricky terrain, the Genius of Girish Karnad embraces brevity. The actual truth is never uttered; it is only hinted at. Shashi Kapoor as Karan Singh gives his most memorable piece of acting by the expressions of his face and the combination of shock and pain in his eyes. The genius is that this iconic scene is shorter than the time it will take for you to read this paragraph.

Karan Singh’s death destroys any possibility of Dharma in the film. Bharatraj reacts violently and becomes distraught on hearing that the person he murdered was his own brother. However, we realize that his pain is not emerging from the ‘Sin’ of murdering his brother. He is in pain because of the ‘Sin’ of his mother having an illegitimate child. He is shattered by his ‘image’ getting wrecked; his ego is damaged. All the while, he is ignorant that all children, including Karan Singh, were a result of the sexual exploitation of Savitri.

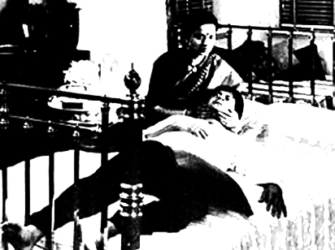

The film is violent without showing any bloodshed. It is designed to make you feel uncomfortable; the secrets that a cultured society keeps horrify us. In the final scene, we see Bharatraj comforted by Supriya as she holds his head on her lap. She asks Subhadra to leave the room, closing the doors on her way out. Shyam Benegal leaves us with an uneasiness about the situation. Saying many things without uttering them.

The film is violent without showing any bloodshed. It is designed to make you feel uncomfortable; the secrets that a cultured society keeps horrify us. In the final scene, we see Bharatraj comforted by Supriya as she holds his head on her lap. She asks Subhadra to leave the room, closing the doors on her way out. Shyam Benegal leaves us with an uneasiness about the situation. Saying many things without uttering them.

On a personal note, this one dialogue in the movie relayed my literal first thoughts from when I first read the Mahabharata. Karan Singh confronts Bhesham Chand to explain all the injustices done to him by keeping him an orphan. The Pitamah counters him and says everyone is bothered by the injustices done to them; what about the others. A worker was killed in a strike action organized by Dhanraj and Karan Singh at the Pandava factory. Bhesham Chand asks, what about the injustice done to him?

In my reading and subsequent viewing of the Mahabharata, this question bothered me. All the central characters in the epic fight and kill each other. Arjuna famously kills Karna, Bhim avenges insult by killing Duryodhana, and we have many more examples. One question always bothered me, ‘Why did so many soldiers have to die in the Kurushetra?’ Couldn’t the key characters of the epic just fight each other man to man? Never during the war did an ordinary frontline soldier kill anyone significant. So why were they part of this war? Everyone was bothered about their kin; the Pandavas mourned Abhimanyu, Kandhari mourned her children, but what about all the collateral damage?

Recently (circa 2021), the Tamil movie ‘Karnan’ has blown the context of the Mahabharata to a complete one-eighty degree. As the name suggests, it is from the point of view of Karna. There have many books written from Karna’s perspective, Mrutyunjay the most famous of the lot. However, they hit a sympathetic note; they make you cry for Karna. Karnan shows what happens when Karna refuses to accept his fate and decides to fight for his own. Karna of Karnan is equal in sacrifice, but he not willing to sacrifice for the sake of Dharma or out of a sense of loyalty to Duryodhana. Karnan is willing to sacrifice for his own lot. In Mahabharata, Karna sought to be accommodated in the rules of the society. In Mahabharata, Karna’s violence is internal; in Karnan, he brings out the violence and challenges society. Society stumbles, fumbles, all appearance of propriety is lost, and its dark side is exposed. Karnan shames society for its violence. A reminder of how fragile our social contract is. Karnan refusal to be a part of the collateral damage comes at a high personal cost. Can he spend the rest of his life happily, or are heroes meant to be happy?

Recently (circa 2021), the Tamil movie ‘Karnan’ has blown the context of the Mahabharata to a complete one-eighty degree. As the name suggests, it is from the point of view of Karna. There have many books written from Karna’s perspective, Mrutyunjay the most famous of the lot. However, they hit a sympathetic note; they make you cry for Karna. Karnan shows what happens when Karna refuses to accept his fate and decides to fight for his own. Karna of Karnan is equal in sacrifice, but he not willing to sacrifice for the sake of Dharma or out of a sense of loyalty to Duryodhana. Karnan is willing to sacrifice for his own lot. In Mahabharata, Karna sought to be accommodated in the rules of the society. In Mahabharata, Karna’s violence is internal; in Karnan, he brings out the violence and challenges society. Society stumbles, fumbles, all appearance of propriety is lost, and its dark side is exposed. Karnan shames society for its violence. A reminder of how fragile our social contract is. Karnan refusal to be a part of the collateral damage comes at a high personal cost. Can he spend the rest of his life happily, or are heroes meant to be happy?

Kalyug, on the other hand, is fatalistic. Whether it is Karna or Dhanraj or even the ever-pained Dharamraj, their fates are sealed. Whether it is Dvapar Yug or Kali Yuga, destinies cannot be changed. Karnan may eventually choose to be happy, but Karan Singh is void of will. Dharamraj and the Pitamah understand the eventual doom in the conflicting paths of Bharatraj and Dhanraj. But they are helpless to stop them. The unruly men conjure up arguments of fairness and justice to silence the wise voices. Kalyug is a commentary on the silence of the innocent voices and their refusal to rebel. In such a scenario, are they the victims of the saga or the perpetrators? It remains a hauntingly open question. This is what Shyam Benegal and Girish Karnad do to us, the audience.

Many authors have tried to redraft perspectives of our mythology by changing its theme explicitly. Isn’t Sita’s Ramayana an oxymoron in itself? It better be called Sitayana then! However, the makers of Kalyug manage to redraft a perspective despite following the myth. Thus Kalyug is one of those movies wherein ‘genius’ turns out to be a relatively weak word to describe what it achieves.

One of my favs ,, I saw it in early 2001 and the pace of the movie amazed me even then