Why do researchers prefer certain problems for continued research than others? The key query is, what is the value proposition in the choice of a particular research topic for pursuit.

The common sense answer could be that the choice is dictated by the value of the solution, in terms of money, in terms of fame, in terms of people affected, rewards, awards, etc. This approach implies a certain novelty in the solution, a newness about it.

However, the reality is quite opposite. Novelty requires unbound imagination, and will result in a myriad of possibilities. Scientific research in a way rejects unbound possibilities and prefers a narrow gaze.

The narrow gaze is brought about by the Paradigm, which cuts the scope of phenomenon under investigation into anticipated outcomes, and scientists prefer this narrow assumable anticipated zone.

Then if a major substantive novelty is not the aim of research (it may be the outcome) *1 , then what is the motivation push for the researcher.

Paradigm defines the scenario and a likely outcome of a scenario, however it does not define how to get to the outcome, how to measure it, how to isolate it, how to formulate it. Thus, the instrumentation needed, the experimental setup, the conceptual and mathematical understanding etc become akin to the missing pieces of a jig-saw puzzle. Normal science behaves like puzzle solving, wherein the endorphin rush for the scientist is in the skill required to solve the puzzle. The validation is in getting the solution, and thus as a corollary the solution must exist.

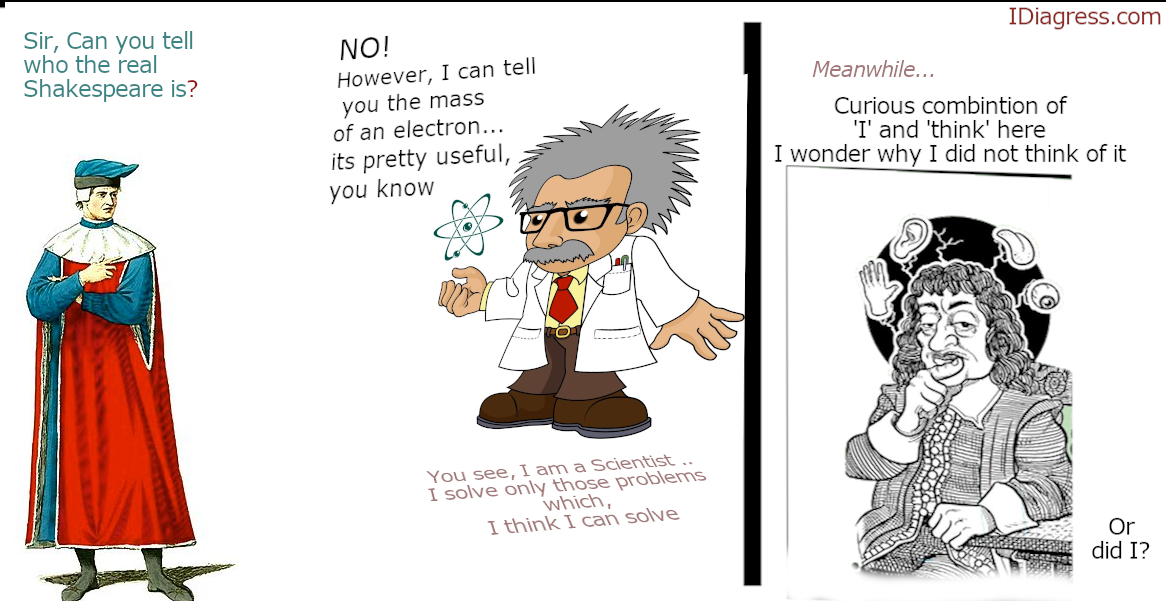

Many might feel that this conclusion is shattering to the commonly held belief that scientists engage in imaginative, out of the box thinking to find solutions to problems where a solution seems improbable. After all, the ‘genius’ of the scientist is to solve for the unknown!

However, the reality is that scientist choose a problem where the solution is somewhat known.

This has consequences, the scientist may seem distant as they stay away from socially important problems as they usually do have a defined solution.

Conversely, this also has an upside, a huge one. The scientist is not distracted by unsolvable, branching problems, and is instead focussed on a narrow band. And this intense focus means rapid development. And it is also one of the reasons why normal science seems to progress so rapidly.

Infomation Box

A contemporary example could be climate change. So far the scientist have rarely pursued a technological solution to greenhouse gases. A way to use existing fuels, with their emissions, and still reduce temperatures. Because at the moment such a solution is improbable and it is easier to propose targets for reducing fuel emissions and usage. Until a paradigm is established that postulates reducing global temperatures despite of increasing fuel emissions, serious research may not emerge. Till then scientific community will be content in measuring temperature rise, creating models for future rise and its consequences.

On the other hand, the same generation of scientific minds is busy creating one large hydron collider after another as the outcomes of two subatomic particles clashing with one another fall within a narrow band.

*1 3p38. “The scientific enterprise as a whole does from time to time prove useful, opens up new territory, display order and test long anticipated belief. Nevertheless, the individual engaged on a normal research problem is almost never doing any one of those things”

No Comment