I was always a believer in the socio-economic theory that population growth declines with rising education and rising living standards. The crude version of this theory is that poor and illiterate people have more kids.

But facts around me belied this theory. Like many in my generation, I have roughly four to five uncles/aunts on either side of my family. In my generation, two kids are the norm. If we go back to one generation, my uncle and aunts also have four to five uncles/aunts. Consequently, we have grandparents whose count far exceeds the scope of the fingers on our hands and legs. But, if we move another generation back to that of my great-grandparents, the widening family tree suddenly shrinks to a couple of branches.

Puzzling, isn’t it? How can the generation preceding the one’s five kids prescribe to ‘Hum doh, Humare doh.’ Were they affluent and educated elites that failed to educate their children!

Thankfully, my great-grandfather lived into his nineties, missing the century mark by a whisker. His cognition stayed firm all through his years, though a bit hard of hearing, he always had a lot to say. I thus got the opportunity to chat with him about his life and times. I asked him, how come you are just two brothers? Maybe there were sisters with whom we have lost touch.

His answer was vague and yet poignant. He said he was ‘probably’ their parents’ fifth child, but the first to survive!

Here is a direct quote from the book that captures this very essence of those times

“children were not counted as permanent members of the family until they had encountered smallpox once and survived.”

India began the twentieth century with a life expectancy of around just twenty for every Indian. Today, a hundred years later, India has raised it to about seventy. A free mind and scientific outlook have helped us increase life expectancy, and hopefully, we will continue this march.

This also puts into perspective the somewhat deceptive anecdotes of how some grand old man climbs a mountain at the age of ninety. Such accounts are usually touted to glorify the sturdiness of the previous generations and point how comparatively weak and lazy our generation is. In those times (like my great-grandfather), if you survived to the age of Thirty, it meant you had a solid genetic make-up. In 1900, around five out of ten children did not stay to celebrate their first birthday. The next hurdle was smallpox, and as the book points out, the age pandemics meant a Cholera or a Plague was always lurking around the corner. Both diseases had a fatality rate that peaked at fifty percent. You needed to be of a robust constitution to survive till your thirties. The Law of averages dictates that if the majority are not surviving a year, and the mean is twenty, some outliers will make it to a hundred. But that doesn’t mean it was all hunky-dory for those who lived then.

This information casts new light on concepts like child marriages. Today these seem evil, but at life expectancy levels of twenty, they are a necessity.

In his book, Chinmay Tumbe brings out the facts and brings out the stories and tales of the pandemics. This is not a paper in a statistical journal; the book is a story with a wide arc compassing the narrative.

The focus is on three infectious diseases that laid havoc in India from 1817 to 1920. Cholera, Plague, and Influenza, three diseases with different trajectories yet competing in terms of the devastation they left in their trail.

The journey of Cholera is a journey in the development of infectious diseases. The various pulls, the prejudices, and the vested interests that play a part in our world.

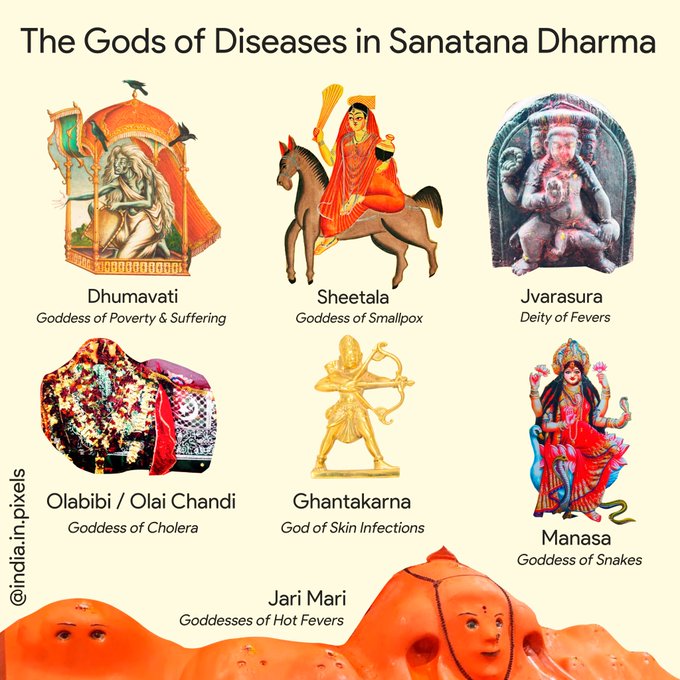

The most important question is, what to do with a disease that you do not understand? If no treatment protocol is available, what does a person do? Obviously, they will explore all avenues. In Bengal, people thronged the temples of Ola Bibi, as she became the reigning deity for Cholera. In Bundelkhand, it was Hurdoul Lala.

With Cholera, roughly half the people made a recovery. However, not knowing why a person recovered creates problems of its own. Treatment based on anecdotes is outright dangerous. If a tobacco addict recovers from a disease, it might encourage everyone to chew on the dried leaves. In Cholera, an outright bizarre treatment was ‘bloodletting.’ Cutting a person’s veins and allowing blood to flow; the more the blood flowed, the more the chances of recovery. One reviewer aptly called it ‘benevolent homicide.’

You might say that ‘traditional’ or ‘archaic’ thinking was the problem, and ‘modern’ science was the solution. Science definitely is the path to solution; however, scientists are the hurdles in that path paradoxically. Scientists who latch on to dogma. The dogma many held on to was ‘sanitarianism’ — a soil-poison hypothesis that theorized that diseases were caused by poisonous ‘miasma’ rising from rotten organic matter. India suffered because British India’s scientific advisor, Cunningham, was loyal to the German miasmic Pettenkofer. For decades people like him either ignored or, worse, actively sabotaged alternative theories for the disease. The land where Robert Koch (Calcutta, 1884) successfully carried out experiments to prove the presence of ‘bacillus’ causing Cholera was ironically the land that was last to accept his work. One can only imagine the unnecessary deaths in the intervening period.

Today, effective oral rehydration therapy (ORT) has brought down the fatality rate from Cholera to well below one percent. With the understanding of Cholera as primarily as water-borne transmission, outbreaks are effectively controlled. We have not seen even a mild epidemic of Cholera in the last hundred years.

The story of the Plague is the same. It also followed the seven stages of a Pandemic. A deadly disease, poor understanding, chaotic administration, misplaced treatments, superstition, science-denial, and final acceptance of the truth. The difference was Cholera tormented India for over nine decades; the story of the Plague unfolded over three decades.

However, Plague has two aspects that are relevant in today’s world.

Anti-Vaxers haven’t changed. After Variolation and Vaccination, we discovered to be effective against Small Pox, Scientists came up with similar techniques to combat Plague. Though mildly effective, these proved to be an effective barrier against Plague. But, rumor-mongering, as usual, played spoilsport in large-scale inoculations. The Anti-Vaxer tactics haven’t changed since then. They target the primal fear of humans: Using words like ‘impotence’ and ‘infertility.’ Effective even during today’s times to keep people away from Vaccinations. Nothing’s changed.

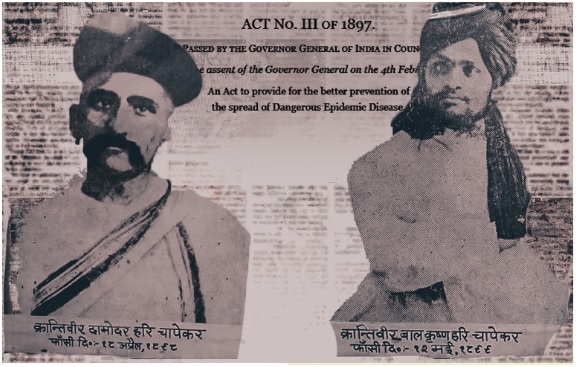

The Second legacy of the Plague in India is the ‘Epidemic Diseases Act, 1897,’ which was invoked again in 2020 for Covid-19. The act is as draconian as an act can be.

It mandated forced quarantines, medical officers were allowed to enter any household for testing its occupants for the disease. Authorities burned down the house of a confirmed Plague case to control the spread of the disease. People were forcefully evacuated and quarantined, lockdowns were imposed.

The events of the last decade of the nineteenth century are a perfect case study of why lockdowns do not work. They did not work then, and they did not work now. The question of livelihoods always drives humans to venture out, no matter what the risk. If you try to scare them, the fear works against any lockdown as the natural instinct is the flight to safety. Plague lockdowns caused mass migrations within India, helping the disease to spread instead of controlling it.

Pune is probably the place that should remind us why harsh measures cannot work. The strict checking and quarantines created immense resentment. Things came to a boil as the Chapekar brothers shot Commissioner Rand in 1897. We must never forget that Walter Charles Rand held the title of ‘The Plague Commissioner.’

Soon the colonial government realized that harsh prescriptive measures will not work. The Epidemic Act though active was never implemented to its full force again. The focus was shifted to awareness programs, co-opting local leaders, integrating preventive work with cultural activities, and garnering the people’s trust.

Reading the chapters on Cholera and Plague, I kept feeling whether I was reading on History or Current Affairs events. With Influenza, the third Pandemic covered in the book, the same pattern was followed, albeit over a period of a year and a half. ‘History repeats itself,’ a hard reality of life. Do we learn from History? Or, as the philosopher George Santayana said, “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.”

The Plague is now a footnote in Renaissance literature. Cholera is a backdrop in Gabriel García Márquez’s love story. Influenza is lost in the chronicles of the first world war. Perhaps they are not where they should be: in the annals of our History books and Medical education. Suppose a generation of people believe that Cholera means just gorging on ORT and some medicines. In that case, they are doomed to repeat the seven stages when a novel Pandemic arrives.

We need to learn from History, but again the Skeptic would say, are humans capable of learning from History. Here are few lines from Kautilya’ Arthashastra. As you read these lines, ask yourself, have we even bothered to implement them —

No one shall throw dirt on the streets or let mud and water collect there.

No one shall pass urine or feces near a holy place, a water reservoir, a temple, or a royal property.

No one shall throw dead bodies or animals or human beings inside the city.

In case of danger from rats, locusts, birds, or insects, the appropriate animals, like cats and mongooses, shall be let loose, and these predators shall be protected from killing.

Poisoned grain may be strewn around, purificatory rites may be performed by experts.

Or, the rat tax, a quota of dead rats to be brought in by each one, maybe fixed.

Isn’t it sad that if all these measures were implemented, the transmission of Cholera and Plague would be largely controlled and other communicable diseases. And interestingly, even today, the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation pays eighteen rupees for every dead rat brought to it.

No Comment